Date: January 17th, 2019

About Tyler Nelson

Tyler Nelson has a lot of qualifications, so I’m going to let his website sum those up for you:

Tyler is a second generation chiropractor whose father was a leader in chiropractic sports medicine for many years. In graduate school he did a dual doctorate and masters degree program in exercise science with an emphasis on tendon loading. He completed his masters degree at BYU and was a physician for the athletics department for 4 years out of school. He currently is the owner of Camp4 Human Performance where he treats clients through his license as a chiropractic physician. He also teaches anatomy and physiology at a local college in Utah and is an instructor for the Performance Climbing Coach seminar series and a certified instructor for gobstrong. When he’s not working he’s climbing or hiking outside with his family.

You can find Tyler in Salt Lake City at his clinic, Camp 4 Human Performance, where he tests athletes, creates programs, and treats all kinds of athletes for injuries.

I met Tyler at Steve Bechtel’s Climbing Training Seminar in Lander in May of 2017, where we were both instructors. Since then I’ve done 3 more seminars with him and 3 other podcast episodes (here and here and here). He is well-spoken and a wealth of knowledge about how the human body responds to climbing and training.

In my 2nd interview with Tyler, he explained how he uses a crane scale to test people’s power output and maximum strength with all kinds of exercises. It’s all about isometric training and testing (pulling on an inanimate object to either gain strength or test your max strength). He wrote 2 articles for us all about that topic:

- Preparing to Try Hard Part 1: Isometric Testing and P.A.P. for Coaches

- Quantifying Isometrics Part 2: Program Auto-Regulation and Its Implications on Finger Training

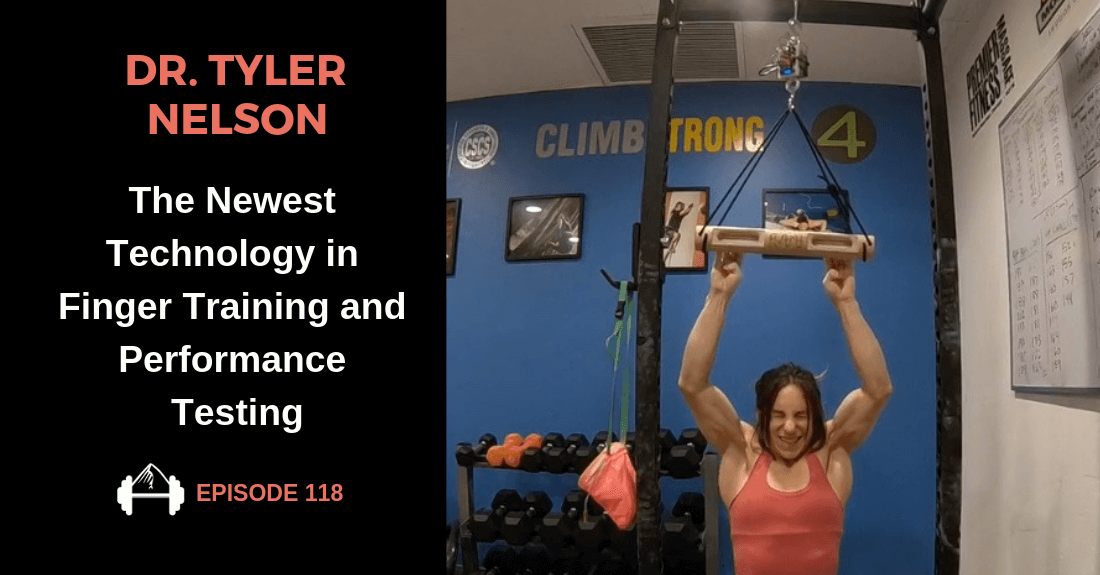

This time on the podcast, we’re focusing on the new technology he’s helped to create and the data you can glean from it for yourself or your athletes. It’s a Custom Strain Gauge called the Exsurgo gStrength500 that includes an app so you can see how strong you are over a period of time. To give you an example, during our PCC events Tyler will test all the athletes with this strain gauage using a fingerboard setup like the one shown above with Alex Puccio. He asks the athletes to pull as hard as they can for 10 seconds or 30 seconds. With the device and the app, you can see how hard they’re pulling and how long they can maintain that force.

The results from this kind of testing can tell you if you’re lacking anaerobic power, aerobic output, or if you just need to be stronger all around. It can also tell you if you’re one of the people who can try really hard, which is good information in itself.

In this interview, Tyler explains everything I’ve described above in detail and talks about the differences between route climbers and boulderers, and how the data can inform training programs for specific athletes. It’s super nerdy and very useful, and if you’re into that kind of stuff this episode is definitely for you.

DISCOUNT CODE: Also, Tyler asked the company to give you guys a discount of $90 off the product and they obliged. The code is “c4hp” at checkout, but please contact Tyler at camp4performance@gmail.com to go through him to purchase it.

Tyler Nelson Interview Details

- Background on isometric testing like this

- Why testing your strength to weight ratio is helpful

- When and why we should use this kind of device

- The new device he helped design

- Why this is better than normal testing and training

- The data he’s gotten from his boulderers vs route climbers

- How it’s changed Tyler’s training on himself and his athletes

Sample Data Sets

On the boulderer and the route climber’s data, compare their “Strength:weight” numbers (3rd item from top on left) and their Max Hang weight at the bottom. You can see that the boulderer’s strength to weight and max hang are much higher than the route climber’s. However, note that the route climber stays at a higher percentage of their max for longer during the 10 second test.

Graph of V14 bouldering athlete on 10 second max pull:

Graph of 5.14 sport climber on 10 second max pull:

Aerobic power graphing metric on trad climber:

This graph is good at representing how a coach would use the strain gauge to prescribe number of reps for an athlete using a repeater program for aerobic power. In this case the athlete drops below 85% after four reps. Therefore if we were to prescribe a repeater protocol for him we would cut it off at four reps. His strength to weightt ratio also indicates that there would be no additional load added to his body because his force does not supersede it often enough.

Climbing Training Seminar with Tyler Nelson, Bechtel, Me, etc..

If you’re interested in being a student at one of Steve Bechtel’s upcoming Performance Climbing Coach seminars, there’s one scheduled for May 18-20th in Fort Collins, CO and you can find more info on it here.

–>> GET MORE INFO

Tyler Nelson Links

- Personal website: camp4humanperformance.com

- Instagram: @c4hp

- Facebook: @camp4chiropractic

- My first interview with Tyler

- My second interview with Tyler

- My third interview with Tyler

Training Programs for You

Do you want a well-laid-out, easy-to-follow training program that will get you stronger quickly? Here’s what we have to offer on TrainingBeta. Something for everyone…

- Personal Training Online: www.trainingbeta.com/mercedes

- For Boulderers: Bouldering Training Program for boulderers of all abilities

- For Route Climbers: Route Climbing Training Program for route climbers of all abilities

- Finger Strength : www.trainingbeta.com/fingers

- All of our training programs: Training Programs Page

Please Review The Podcast on iTunes

Please give the podcast an honest review on iTunes here to help the show reach more curious climbers around the world.

Photo

Tyler Nelson photo of Alex Puccio using the ExSurgo gStrength500 in Tyler’s clinic.

Transcript

Neely Quinn: Welcome to the TrainingBeta podcast where I talk with climbers and trainers about how we can get a little better at our favorite sport. I’m your host, Neely Quinn, and I want to remind you that the TrainingBeta podcast is an offshoot of the website trainingbeta.com that I started that is all about training for rock climbing.

Over there you’ll find a regularly updated blog, you’ll find training programs for rock climbers that are online and easy to use, you’ll find online personal coaching with Matt Pincus, and nutrition coaching with me. I hope that all these resources together, along with the podcast, will help you become a better rock climber. You can find that at trainingbeta.com.

Welcome to episode 118 of the TrainingBeta podcast. Today I’m talking again with Doctor Tyler Nelson. Tyler Nelson has been on this show a few other times and I have him on the show so often because he’s really smart, he’s a good teacher, he knows what he’s talking about, and he has a lot of data to back up what he introduces to us. He has introduced to me, at least, BFR so blood flow restriction training, and also isometric testing and training.

What we’re going to talk about today is kind of an expansion of what we’ve talked about in the other episode and his articles about using isometric testing to figure out how strong you are and also to figure out how you need to train to get stronger in certain areas.

I’m going to let him do a lot of the explaining of this new device that he’s been developing and the app that goes along with it and the data that comes out of that app.

Just basically, we’re going to be talking about a custom strain gauge made by this company, Exsurgo. Specifically, the gStrength500 device. It’s basically a scale that tells you how hard you’re pulling on something. With that he’s gotten some really cool data about a) how hard we can try and for how long, b) our strength-to-weight ratio, which is really important, and the differences between boulderers and route climbers and trad climbers. He’s going to talk all about that and how we can use this device, or something similar to it, as trainers or as just climbers trying to get stronger.

The device he’s going to talk about is not cheap. It’s like $900 with the app but I think it’s a really good introduction into what the future might hold for climbing training and climbing coaching, more specifically.

I hope you enjoy this interview. Tyler talks really quickly. I try to slow him down and I try to ask the questions that I think you might be wondering because he just thinks fast, he talks fast, and that’s part of what makes him so smart. Enjoy and I’ll talk to you on the other side.

Neely Quinn: Welcome back to the podcast, Tyler. Thank you very much for talking with me again today.

Dr. Tyler Nelson: Oh yeah, I’m happy to be here.

Neely Quinn: For anybody who hasn’t listened to your other podcast interviews could you just intro yourself?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: You bet. My profession is I am a licensed chiropractor in Salt Lake City. I did a dual doctorate/master’s degree program in exercise science so I’m really interested in exercise physiology. Out of my clinic, which is largely musculoskeletal care for any types of pain complaint stuff, I have a strength and conditioning business where I’m really interested in some cutting edge science behind testing rock climbing athletes.

Neely Quinn: That’s one of the main reasons that I like having you on the show. It’s because you talk about things that other trainers don’t even know about yet and you’re actually using them in your clinic because you have full reign over what goes on in there. We’ve talked about a few things like that but what are we going to talk about today?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: Today we’re going to talk about – I think in one of the first or second episodes we talked about using a crane scale to measure peak force in climbing athletes for a couple of specific types of movements, just as a way to gauge maximum finger strength or maximum pulling muscle strength. Today it was my idea to talk about a custom strain gauge that’s now going to be available for purchase in mid-February. It’s kind of like the piece of tech that climbing coaches have wanted for a long time that understand testing athletes. That’s going to be available so we’re going to talk about the ins and outs and the difference between using that versus using the old ways to quantitate finger strength and capacity.

Neely Quinn: So you said it’s a custom strain gauge. What is it? What’s it called? Where can people find it? When is it going to be available?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: It will be available mid-February and it’s manufactured by a company called Exsurgo USA. Maybe a year ago – I’m not exactly sure of the time frame – Greg, the developer, reached out to me and was like, ‘Hey, I have something I want you to to prototype test for me and develop some protocols for testing with this tool.’ He sent me the first prototype of the head – for the clinics that people have been to it kind of looks like a bomb. It literally has loose wires and it’s a custom strain gauge with a little readout on the front that displays numbers. It’s really cool looking.

That was the first one that was made and he sent it out to me and over the year we just kind of communicated back and forth about development and what athletes and coaches are most interested in and what was the best sample rate and the actual maximum kilogram readout that it can tolerate, the load cell capacity…

So I’ve been using that for the past year and come February this thing is going to be actually packaged in something that doesn’t look like a bomb and it’s going to be able to be purchased by coaches. I’m doing some series where I’m going to climbing gyms and I’m teaching coaches how to use it. It’s a really powerful tool that can be used for measuring climbing athletes but it’s kind of like you don’t know what you don’t know until someone teaches you what you don’t know. There’s a lot of things that can be done with it that we’re going to be showing coaches how to do.

Neely Quinn: Okay, so for full disclosure’s sake, I’m curious if you’re being paid by Exsurgo?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: No. The company sent me the tool and they’re going to give me the proceeds of the application that is climbing-specific. I don’t have anything to do with the manufacturing of the tool but for climbing coaches we’re going to try to make development specifically for climbing coaches that gives climbing coaches the exact readout information that they’re looking for and for that I’ll make the proceeds on. I essentially made that whole template.

A lot of people that follow me on Instagram or whatever, I have a huge spreadsheet that probably took me 80 hours to make that really kicks out a lot of really valuable data on athletes. I made that solely, by myself, based on raw numbers that were coming from this. After this was being manufactured, Greg reached back out to me and said, “Hey, I want to make a climbing-specific app. You’ll receive proceeds from that.” The actual product itself, I have nothing to do with.

Neely Quinn: That’s pretty cool, though, that you’re able to partner with somebody to make something that is so applicable to your athletes.

Dr. Tyler Nelson: Yeah, it’s really cool. There’s a couple of other coaches around the world that are doing something similar and this isn’t the only product out there that does this, this is just one that’s going to have raw information. The one thing that you don’t want with a custom strain gauge is you don’t want the strain gauge to smooth out the data. You just want it to kick out raw numbers because the data is a little more accurate. There’s going to be options with this one, whether we develop the application for it or if people just purchase the unit and it kicks out raw numbers, then they’re going to be responsible to do whatever they want with it and coaches that really understand the value of that information can do whatever they want with it.

For me, I’m kind of ahead of the game in terms of I’ve had one for a year and I’ve been playing around with it and testing people and finding the best protocols. A lot of times, and I would do the same thing, it’s just easier to go off of what someone has already done. That was kind of them reaching out to me and saying, “Hey, we want to use your methodology for this and be able to sell it to our customers.”

Neely Quinn: So let’s back up for people who don’t know what we’re talking about. Sorry we’ve gone so far into this without fully explaining it. Run me through the process of how you test one of your athletes with this.

Dr. Tyler Nelson: We can test pretty much any movement that you want because the cool thing about this particular strain gauge – the other research-quality strain gauge would be a force plate. A force plate is something that you stand on so it’s fixed onto the floor or you can hook them to other objects. They’re pretty bulky and they’re very restrictive in terms of being able to travel with it.

This strain gauge can fit in my luggage very easily and I can move it around in a gym or I can travel with it, so it’s very flexible in terms of the positions that you set an individual up for while testing. We can mimic the similar positions that we see while we’re rock climbing and any type of movement. You can do horizontal pressing like a bench press, you can do horizontal pulling like a seated row, you can do vertical pulling like a lat pulldown or a pull-up machine, you can do a deadlift isometric which is the same thing as doing a deadlift with a bar, and you can do one-arm, two-arm, you can change the edge size of a hold or any sort of product that you’re using to pull against.

You can really measure peak force of any type of athletic movement that you would want as a coach. The flexibility with this particular product is fantastic because if an athlete has a specific weakness, a coach can specifically target that particular movement and they can measure it. They can measure over time to actually track whether that athlete is making progress or not in that movement. It’s very endless in terms of the types of things that you can do with it and it measures peak force.

We’ve already talked about the crane scale in a previous episode. The crane scale is very good at measuring peak force and I have a lot of people buy it from a distance because it’s very durable and they’ve been very well tested so they’re very accurate, but the downside with a crane scale is it doesn’t sample at a very high frequency. It’s not good at measuring power or it’s not good or able to measure force over time where the real cool thing about this particular product and other products like it on the market, it can actually measure the force over time.

The one that I have currently, we’re having sampled at 95 milliseconds. Every 95 milliseconds I get a readout of my athlete doing their particular movement that we chose.

I chatted with Greg recently and the one that’s going to be purchased, and he’s trying to work on the software behind this, it’s going to be where the coach or the athlete actually chooses the sample rate. If you wanted to do a contact strength measurement you could drop the sample rate to 25- or 50-millisecond readouts and if you wanted to do a 10-second effort or something longer, you could change it to 100-millisecond readouts so you don’t have as many numbers to sift through.

Neely Quinn: Alright, so this is important for both testing an athlete and then testing their progress on the training program that you or another coach will give them. Anything else that it’s important for?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: It’s really important for tracking fatigue, too. It can be a mechanism – if you had one of these set up, and this is what we teach at the PCC seminars. One of the most important functions of having something that’s really easy to test, for people that have done other types of lifting or powerlifting movements, to do a one-repetition max takes quite a bit of time. If you were going to do a one-repetition on a deadlift it would take you maybe 30 minutes to complete that one-repetition max because you’ve got to slowly add load to the bar and get ramped up to where you’re actually doing a one-rep max. By the time you actually get there you’re going to be a little tired because you’ve performed all that other work before the one-repetition max effort. It takes a little bit more time.

Isometric is usually an overestimate of a one-rep max by, the science would say, between 10-20% of an overestimate of someone’s one-rep max. We can use this as a way to really quickly quantify someone’s one-rep max in something that’s very specific to their sport and them individually, but we can also use it if it’s set up at a gym. It’s very easy to set up and you can test someone even every day or every other day to actually measure their amount of fatigue.

The other way that people classically measure athletes is by doing jump testing and doing a vertical jump test, which has been documented to be a pretty accurate form of measuring fatigue. When it comes to the measuring aspects, you need something that’s a little more accurate like a force plate or something that actually measures flight time versus just slapping a wall or something that’s not as accurate, but nonetheless those are still measures of athlete adaptation and fatigue. So, you could also use it for measuring athlete fatigue.

Neely Quinn: Okay, and just to be clear, the jumping is a completely different tool than what we’re talking about.

Dr. Tyler Nelson: The same company makes a similar tool for jumping that I also bring to the PCC seminars. That’s the same jump tool that I have called the G-Flight. I use that as well in my office because this company is really cool and they’re all about trying to make tech affordable to coaches. A research quality strain gauge, like the gStrength that I have here, is $10,000. They’re really expensive. To actually get those into the hands of climbing coaches is very challenging. They cost a lot of money so they’re all about creating tech that’s affordable for coaches, which is really cool.

Neely Quinn: Right. Speaking of which, this Exsurgo strain gauge that we’re talking about, how much is that going to cost?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: I think right now they’re pre-selling them for $899 so with the app or the extra info I tell people $1,000, which is still a good investment. It’s not something that’s as cheap as the crane scale, which is $150, the one that I like that’s really durable. There’s a big price difference but the amount of information that comes out of it and the specific programming details that come as a consequence of using it are totally worth the money. There’s no questions asked that it will be the best possible assessment tool for climbing coaches. That or other products like it. The cost for it seems like a big expense but when you understand what it can do and you understand how much actual research-quality strain gauges are, it’s not a big deal.

Neely Quinn: And maybe if a person worked at a gym as a coach, maybe it’s something that the gym would invest in.

Dr. Tyler Nelson: Yeah, the gym for sure. Gyms spend lots of money purchasing Moon boards and Kilter boards and Lattice boards for boards to climb on and to do assessment stuff so this is just another assessment tool that maybe needs a little more oversight so people don’t break it or walk away with it because it’s pretty portable.

For youth climbing team coaches – I have a couple of these set up this spring already where I’m going to the gym with mine and gyms are buying them and I’m just setting up and we’re measuring athletes and we’re selling tickets for people to come and get assessed and tested, then teaching the coaches how to do it.

Neely Quinn: Is that something you’ll do other places in the United States?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: Yeah, I have one set up in Philadelphia and I have one set up in Connecticut and maybe one in Amsterdam in February. I’m talking to someone from New Mexico, I think, that’s interested. They’re just local gyms that are interested in doing better athlete assessments that want to learn how to do it safely and properly that maybe don’t have the science background that I do.

Neely Quinn: Right, I mean that’s the problem, right? Coaches are going to listen to this conversation and be like, ‘It sounds great and I would love to use it but I don’t maybe even trust myself to use something like that properly because I don’t have the training.’ How do people get the training?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: You get the training, ultimately, by reading lots of research papers, right? Studying not even physiology textbooks, because those are usually outdated, so the best way you can do it is maybe by listening to exercise science podcasts. There’s a couple out there. There are ways you can get good information, it just requires a lot of work. It requires a lot of effort and a lot of times the path of least resistance is just to learn from someone that knows more about it than you.

I’m not saying that I’m the person that always knows more than other people. I do the same thing. I find someone that I think they know more than me and I really pay attention to them and I follow what they’re doing, then I manipulate it to what fits my athletes and my clientele. Learning from other people is the best way to do it and reaching out and having that open conversation. Going even to the PCC clinics that we teach, I learn tons from the coaches there. Every time we do one there’s different information that people are talking about so just having that open communication with people is a good way to do it.

When it comes down to the science stuff and the testing metrics, that comes from reading research journals. I’m kind of a nerd for doing that kind of stuff and it’s what my master’s degree is in so I’ve had the schooling behind it to do that.

Neely Quinn: So it isn’t something that a coach should just pick up and start using.

Dr. Tyler Nelson: They can pick it up and start using it. There’s a couple basic things that they would want to understand. Most coaches are smart enough to know that measuring peak force is a way to quantify how much recruitment, or size, or both that an individual has in a particular movement. We do it all the time on a hangboard already.

We assume that someone’s one-rep max is them hanging on a board for x-amount of time and we add weight until they can’t hold onto that edge at that finger position for that time. We try to quantify maximum finger hangs by doing it the old way where we’re just adding weight, where this just bypasses that process and makes it very quick. It gives you a lot more information if you know how to understand what you’re looking for, but most coaches have a basic understanding of that. It comes down to the real difference between measuring force versus just trying to subjectively watch an athlete and estimate when they’re failing or when they’re fatiguing.

Neely Quinn: Can we go through a few athletes of your’s and what you found from the testing and then what you did consequently?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: One thing that’s really interesting is there are a lot of really high level boulderers in most states like Utah that have lots of rock climbing. I get the opportunity to test a bunch of them in the office so it’s pretty interesting. Just this last year I’ve been able to test some V14 boulderers and some 5.14 sport climbers.

The number one thing that I like to talk about at the PCC for people to understand is if you’re trying to do a 10-second max weighted hang for better finger strength, the way that they’ve classically done it, that was in Eva Lopez’s research, is they just started adding weight until they couldn’t hang on for 13 seconds anymore. They use that additional weight added to their body as their maximum weight for a weighted hang. That’s really just watching a timer and watching them hang.

If you use a custom strain gauge and you have someone seated and they’re vertically pulling as hard as they can, very similar in the amounts of stress and force that go through the fingers, you’ll see that they’ll usually hit their peak at around 2.5-3 seconds but then the rest of that time is them just fluctuating around that peak. It’s very rare – I’ve maybe seen it once – that athletes will ever hit that peak force again.

For me it’s all about finding ways to better train and assess athletes so we can make people’s fingers hurt less. I see all the downsides of climbing so much when people have finger injuries. If I can have an athlete do a 10-second pull as hard as they can, I can better calculate their hang weight. Instead of just choosing a peak force that I see them do I can take the average of a percentage of that force and subtract their body weight and give them a better, more accurate weight they can use to hang off of.

The whole point of doing a finger training program is to increase the muscular recruitment in the finger flexors so in order to do that, if I’m just watching them and I’m choosing a weight, there’s no guarantee that they’re actually producing that much force in their finger flexors. They could just be hanging on their soft tissues which is really stressful on the fingers versus if I’m using a strain gauge, I can accurately see how much force they’re actually capable of producing for 10 seconds. Therein lies the big distinction: the difference between – you could take someone and hang a huge amount of weight off their body and they could hang on their fingers, but that does not tell me that they don’t have the capacity to actually produce that much force for a total of 10 seconds.

Neely Quinn: And that’s kind of what you’re wanting to see, right? If they’re getting their max at 2.5 seconds and they’re sort of wavering for the rest of the 10 seconds, you want to see that, over time – what do you want to see?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: Therein lies another thing that I kind of do differently now than a lot of climbing coaches in terms of finger strength testing. If you talk about making fingers stronger we’re talking about better recruitment. We usually get better recruitment by just trying as hard as we can or doing a one-rep max but 95% of people hit peak force at 2.5-3 seconds.

If I’m trying to make my fingers stronger by getting better recruitment, there’s no reason to pull longer than 3-5 seconds. There’s no reason, if you’re trying to get better recruitment in your fingers, to hang on for 10 seconds because after you hit your peak force you’re no longer recruiting more motor units, you’re no longer recruiting more muscle fibers, you’re just training the metabolic energy systems that supply work to the muscles. That’s an important thing to train as well but if we’re trying to keep our fingers less injured and we’re trying to make them stronger, we can use these basic principles to say, “Wow, it never takes 7-10 seconds for someone to do a one-rep max of a particular lift. It usually takes between 2-4 or 5 seconds at the max.” We can really fluctuate our program prescription to athletes based on what we’re trying to do. As a consequence, hopefully we can get people stronger without getting them injured so much.

The tricky thing about any hangboard program is people don’t know when to stop or they don’t know when to change their program. A coach doesn’t know, either. There’s a lot of really smart coaches that are climbing coaches that give someone an exercise program that has finger training in it and they don’t know the exact time when to quit. Every athlete is a little different so if we have a way to measure them and re-measure them, it’s really easy to identify when an athlete has plateaued and we can switch up the program.

Neely Quinn: So you said that you were doing something different than other coaches. Were you talking about the amount of time?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: Yeah, like the recruitment. For me, if people are doing a recruitment, I have them literally do an isometric as hard as they can for 3-5 seconds and then I have them track and measure each effort.

Neely Quinn: With a lot of rest in between.

Dr. Tyler Nelson: Lots of rest in between, yep. If it’s a 3-5 rep it’s usually 60-120 seconds rest in between. Depending on the athlete, I have them do between 3-5 repetitions of one finger position then I change the finger position and then we do that again. I have them track it over time. You don’t need a higher tech tool like the strain gauge that I have, you can do that with a crane scale. As a way to differentiate how to see that, you would see that with a better strain gauge like the Exsurgo one.

The only way you can tell that someone has really hit their peak force that fast and that it’s not changing is if you have the ability to measure force over time.

Neely Quinn: I guess what I want is for people to come away from this knowing is sort of what this would do for them. I just want to know – it seems like sometimes you are having people do the isometric pulls and you’re sending them home and you’re like, ‘You’re going to put this much weight on you when you do these hangs and you’re only going to hang for 3-5 seconds.’ Right? So it’s either/or? Either can work?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: Yep, either can work. You can easily add weight to your body and hang for three seconds and get better recruitment.

Neely Quinn: So after they do that for a certain amount of time or sessions, you’re saying they’ll come back and their max force is going to be greater?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: Yeah, it should for sure. That’s the whole point of doing finger training. When we talk about finger training we’re making adaptations to the muscles, mostly which happen fast, but long term, years on years, we’re making adaptations to the tendons. We want to make adaptations to the muscle and we want to stress the tendons and pulleys as little as we can so we don’t get them injured so we can continue to do that over many years. Every time we get a finger injury we get kind of set back a little bit and the fingers and the brain become more engaged in the idea that the fingers hurt and we have weakness there.

Neely Quinn: Right, and then at some point their max force has increased and then you can tell them, “Okay, you’re going to increase your weight that you add to your body by this much and then we’ll retest in a certain amount of time.”

Dr. Tyler Nelson: Yep, that’s one good application for it. You don’t really need a cool tool, really, to do that. I have athletes do that from a distance where they’re just using a crane scale and they can measure peak force and track it over time and then know when they need to switch up and know when they need to take a couple de-load weeks or a de-loaded week and then maybe one back-to-back, because they’ve reached a plateau and they’re not adapting anymore. Then you need to change up the stimulus.

The tricky thing that’s annoying for athletes and coaches is in order to create adaptation long term, you always have to switch the program every 4-5 weeks. Some people can tolerate more volume and more time on the program. It just depends on the individual. You always have to switch things up to keep the body interested and to keep the body adapting to the stress.

Having a tool like this allows coaches the better opportunity to be more prescriptive with where the athlete needs to go and that’s just one thing. We can chat about more like the aerobic power and anaerobic capacity testing. Therein lies the real differentiator between this and just a rudimentary crane scale.

Neely Quinn: Okay, but the main difference between people who either don’t have a crane scale or this and they’re just using max testing is they’re doing the standard where they just add weight and add weight until they can’t hold on any longer. That’s what a lot of coaches will use to test their athletes after they’ve done a cycle of finger training. What you’re saying is this is better because you can test them more often to see if they’re plateauing or if they’re getting better?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: And you can train like this, too. I’ve done lots of training with the strain gauge where I do all of my finger strengthening measuring all the forces. That’s a little bit over the top for most coaches that have maybe teams of athletes. It’s not feasible but you could certainly do that if it was at a gym and they had access to it. The real big difference there is when you’re pulling and you’re performing an isometric for 3-5 seconds you’re autoregulating how much force you can put through your fingers. If you are hanging on a weight or hanging on a board with x-amount of weight on your body there’s no guarantee that your muscles are actually producing equal amount of force to overcome that resistance.

Therein lies the real big difference between pulling on something that’s moveable that’s hooked to a scale, or not even hooked to a scale, versus hanging with a certain amount of weight on your body. When we pull on something we can guarantee that the amount of force that you are putting through your fingers is only as much as your muscles can generate in any given time. Technically, that would mean that it’s way safer than hanging with a bunch of weight off your body. That doesn’t mean that hanging with a bunch of weight off your body doesn’t help, because it has for years and it makes people really strong, but it’s just other ways that we can train maximum finger strength.

Neely Quinn: So going back to the Exsurgo app, because we haven’t really talked too much about what the data is that it will actually spit at you, tell me about that. What kinds of things are you getting from these sessions with your clients?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: My Excel spreadsheet that I created with mine that I do, I usually measure whole body strength with isometrics. I’ll measure a low pin position and then a mid-thigh pin position, which is a way to measure a deadlift isometric which is essentially a whole body tension measurement. I’ll do those probably a couple of attempts so that if the athlete feels like they’ve got a little bit more we can do two or three.

Then I’ll do a vertical bar pull. We’ll do pull muscle maximum strength and we will have someone grab onto a lat pulldown bar with a scale and they’re going to pull as hard as they can. We’re going to get that measurement and we’re going to do a strength-to-weight ratio on the pulling muscles.

Then we’re going to do a finger, 20-millimeter edge, maximum strength test where they’re going to bring the force on slow, 3-5 seconds. We’re going to calculate that and it gives them a strength-to-weight ratio score and it compares the difference between their vertical bar pull versus the 20-millimeter edge pull to be able to differentiate. Some people’s finger pulls are almost as strong as their bar pulls which means those athletes would probably benefit from working on pull muscle strength. Usually it’s the opposite way around where the pull muscles are much stronger than the finger pull efforts so then we need to build up maximum finger strength.

Then we’ll do a contact strength measurement. What’s really, really cool about this particular product that other products don’t do well is measure contact strength. The exact body position and methodology is still not in much literature in the climbing community. I know I’ve been doing a bunch of it and some other coaches have been doing some of it where you can have them have no force on the particular hold that they’re using and then you can bring the force down as fast and as hard as you can for one second.

The best literature now would say you take five measurements of an athlete at one-second effort and you take the best three attempts and you take the average of those. You want to calculate those averages under 100-200 milliseconds. There you see a custom strain gauge that can actually measure the amount of force that someone can produce really rapidly and under 200 milliseconds. I do that with all my athletes and they get that done.

Then we move onto anaerobic power testing where I’ll have them do a 10-second effort where the effort is as hard as they can go for 10 seconds and it gives me an estimation of their anaerobic power. That’s like the ATP-PC system, how much power they can generate for 10 seconds.

Then, I’ve classically had them rest for a while and then do a 30-second maximum effort test which is a way to calculate anaerobic capacity or some people call it ‘critical power.’ That, essentially, is a measurement of the intensity or the time at which they drop below a certain percentage of that maximum which gives me an estimate of how long they can work at the highest intensity before they need to rest. If you’re trying to work someone at some sort of intervals on a campus board or systems board or a Moon Board, or trying to build their capacity, you would work within that time frame because you know beyond that you’re just going to drop below that percentage so you’re not going to get as good of an adaptation. You’re just going to end up making them really tired.

Lately, I’ve kind of liked the idea of doing 6/3 repeaters for 10 sets which is a way to measure their aerobic power, so the ability to reproduce high intensity efforts to see how many sets of that they can do. You can use that data for hangboarding or you can use that for power intervals on a Moon Board or Tension Board.

The cool thing about having the raw numbers is coaches can do whatever they want with it. What I’ve done with mine is I made my Excel spreadsheet so it kicks out averages, it kicks out values above 90%, values above 80%, takes their strength-weight-ratio and calculates their hang weight on all of these. With the raw data you can get really, really technical with it and I’ve done that with mine. Most coaches that I’ve talked to about it, because a bunch of people have preordered these already and they’ve contacted me, they’re like, ‘Can I have your spreadsheet after this to use?’ I’m psyched about that and for people to use it because it was a lot of work to put together and it was really well thought out.

Neely Quinn: Have you done this on yourself? I mean, I know that you have…

Dr. Tyler Nelson: Oh yeah, for sure. Right now I haven’t been training my fingers aside from this new woody that I built in my office because this 45° woody is really hard on your fingers. I haven’t been training my fingers lately but before that, I’d go through a whole cycle where I would measure all of my finger strength training on the tool and I can measure everything. It’s not totally necessary but it’s really insightful and I learn a lot from doing it on myself.

One thing that took a really long time for us to do was measure contact strength. It seems scary to have no force on a board and then pull as hard as you can on a board. It seemed kind of scary and I’m sure we’ve mentioned this but I usually try things on myself before I do others. A lot.

Neely Quinn: What have you found about your own weaknesses and strengths? How have you found it out and then what have you done about them?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: My weakness for sure is that I’m classically a trad climber so I never, up until three or four years ago, have been serious about training my fingers. My fingers aren’t as strong nearly as some of these high-end boulderers so I’ve been working lots of different finger training programs on myself. I use the maximum effort isometrics frequently, I use the volume finger training, or what I call volume finger training, where I fluctuate. I’ll do a 10-second effort on myself because I think there’s some value in hanging for 10 seconds or even longer than 10 seconds but there’s no value in hanging the same weight for that time, the whole time.

Usually, if I’m going to hang for 5 seconds I have x-amount of weight. If I hang for 7 seconds I change the weight. If I hang for 12 seconds I change the weight so I cannot injure my pulleys and so I can get adaptation. If you look at the force/time graph you can see that there’s no way that I’m producing the same force that whole time. I’m safer to train my fingers for metabolic adaptation in my forearms by fluctuating that weight with the time under tension.

Neely Quinn: So you can test yourself and see how much force you’re producing at 12 seconds and sort of go off that with how much weight you put on you.

Dr. Tyler Nelson: Yep. You can measure your peak force, you can take the average over 5 seconds, average over 7 seconds, average over 10 seconds, and subtract your body weight from that and that gives you a better estimate. You can do more volume of hanging if you’re crunched for time or you can’t get to the gym or you want to just really focus on your finger training. You can also change when you hang for longer when you change that weight. There’s really no way to know that unless you have some way to measure force over time.

There’s no way to tell how much you can do other than trial and error and for people with busy schedules, trial and error can be a real waste of time. When I was younger I could get away with doing stuff like that but nowadays I don’t have time for trial and error so we just kind of cut to the chase and measure things and be really quick about it and efficient.

Neely Quinn: Yeah, I feel like nobody really has time for trial and error these days.

Dr. Tyler Nelson: I don’t think so. Most of the climbers that I see here that are my age – the only people that have time are high school students. That’s even questionable, really, how much time they have. Or even early college students. Most of the adult climbers that I do programming for, they’re just as busy as I am so everyone wants to get stronger and they don’t want to get hurt and they want to know that their program is making them stronger and they’re achieving their goals. They’ll be psyched.

Neely Quinn: Yeah. Is there any rule of thumb that you use? Like, if I were to do a 10-second max pull and measure that and it said that I could – I don’t know if this is realistic because I can’t remember the numbers, but if I weigh 110 pounds, it might say I could do 120 pounds, right? At my max? I have no idea. Then you subtract that from my weight so it’s 10 pounds. Would you say that I should then do a 10-second hang with 10 pounds on me, or what is the percentage of that that you’ll use?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: It just depends on your effort. It depends on how long you can produce 90% of that weight for 10 seconds or 80% of that weight. That’s when the coaches have the option to choose the percentage that they want their athletes to work under. If you want to work someone’s aerobic power you want to work them at 90%. If you want to work someone’s anaerobic power you would work them at 80%. You can actually fluctuate the amount of tension and the amount of weight that you would put on them based on their performance.

There’s been some really interesting youth that I’ve tested. Some of these youth athletes weren’t producing much force over body weight but they could stay at 90% for 10 seconds.

Neely Quinn: Okay, so what would you do with those athletes?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: Those people for sure don’t need to hang weight off their body. Those athletes could just do body weight hangs. Like with youth athletes, the other thing with the local teams here that I work with, if you test youth athletes it’s really interesting to see the amount of force they can actually put through their fingers. I think some of the youth athletes here – even 16 year old females that have been in Nationals regularly, really high level youth sport and boulder climbers – some of them had estimated hang weights of 70 pounds off their body. Hanging 70 pounds off a youth athlete’s body? No coach is going to do that but that doesn’t mean that they’re not producing that much force through their fingers when they’re trying as hard as they can on the wall. It’s very likely that they might be.

In order to keep youth interested in training and make sure that they don’t train outside of your prescription or the coach’s prescription, we’ve been like, ‘Okay, let’s do some finger training for these athletes because they want to do it and they feel like they need to do it.’ Maybe they do or don’t but they’re going to do it behind the coach’s back most of the time if we don’t give them something to do.

We tested all the athletes and we lowballed all the numbers and we gave them some weight to hang off their bodies on their fingers. As long as the volume is kept low, there’s no real risk in doing that. It’s more risky to have them climb on their own for extra days for more volume, in terms of injuring their fingers, but the force capability of those particular athletes definitely has that possibility.

Neely Quinn: But if you’re lowballing the number isn’t that not doing anything for them? Isn’t that just tiring them out?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: Not necessarily. By lowballing I mean 15% lower than the actual max. We had them hanging with maybe 50 pounds on their body but it was a really low session. You can still get good adaptation with that. They can still get good tendon stiffness, they can still get work on their recruitment, and it’s another way to know.

Even on the wall, one of the subjective responses that the athletes had when they do 30-second maximum effort is they felt like it was a very similar experience to when they were gripped on an onsight level sport climb or when they’re at a crux. That’s how hard they felt like it was so the likelihood that they’re doing that already is definitely possible.

In order to push athletes, the tricky thing is the difference between adaptation and injury is a really fine line. In order to get athletes to adapt, we need to get them really up close to their limit level. That’s pretty scary unless you have a good way to measure athletes and their capabilities.

Neely Quinn: So unfortunately, it’s still a guessing game as to what’s actually safe, especially for kids, and what’s not safe.

Dr. Tyler Nelson: Yeah, and I think there are some other coaches as well that I know that have youth teams that put weight on their kids and load them. I’m not a youth team coach so I’m not exactly sure how much of a load the coaches here put on their athletes individually. That’s out of my realm. I don’t have any say about that but really it’s just the testing and I give recommendations or options as to what these athletes can tolerate to the coaches. Then ultimately it’s the coaches and their kids’ and parents’ decision.

Based on the testing numbers it would be okay to add weight to some youth athletes’ bodies while they’re hanging on their fingers. Not everyone, for sure, because the other athlete that had no extra weight added to her body, she wasn’t producing much more force than her body but her effort was incredible. She was able to stay above 90% for a full 10-second effort.

Neely Quinn: There were some like that in the last PCC event, too, and I thought that was really interesting because you were basically saying that some people can do that and a lot of people can’t. What do you do with that athlete who can sustain that force for so long, even if it’s not that much force?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: You can work on her finger strength still but you would probably want to work on her skills. That athlete is good but I’m not sure that she’s placing in Nationals and I’m not sure that she’s performing as well as her peers so she would probably be someone that you could really work on the skills of climbing with. You could make her fingers stronger, too. You could slowly start increasing the load and adding some extra weight to her body when she’s hanging on her fingers at a low volume but it gives the coach lots of insight into that athlete.

Tried and true the coach will say, “That athlete has a huge heart. They try super hard,” and that’s great. Then you know exactly which direction to take that athlete. You can say, “Hey, your effort is amazing. Let’s make your fingers a little bit stronger and let’s really work on your climbing movement.”

If you have an athlete that’s got crushingly strong fingers and they’re not performing well, say, “Wow. We really need to work on your climbing skills.” It’s usually the opposite way around where they have really good skills and they don’t have strong fingers for most people. Most people are like, ‘Cool. I need to make my fingers stronger while I simultaneously work on my body tension and my skills.’

Neely Quinn: That was another thing I was going to ask you about because you said this athlete has really strong fingers, but the fact is that a lot of people would get this tool and they would measure themselves and they’d be like, ‘I don’t know if this is strong or not. How do I stack up?’ Do you have data on a bunch of different levels of climbers? Is that available to people?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: I do. I have lots of data on it. The problem with the numbers that I have is over the past year and a half I’ve had four different scales that I’ve used at any given time just because I’m trying to sample what I like and what people have exposed me to. I have a crane scale that I have tons of measurements on then I had a different type of crane scale that I did some on. I have one of those Tindeq Progressors that I did some testing on. I had two G-strength from Exsurgo tools that I’ve done some testing on. You’re not always measuring apples to apples if you use a different scale

Really, what athletes are most interested in for climbing is their strength-to-weight ratio so it doesn’t really matter what someone’s force production is. It much more matters what that percentage is of their body weight.

Neely Quinn: What are some parameters for that? What is ‘good?’ What is not good?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: It depends on the test. Most really high level boulderers, their finger maximum strength-to-weight ratio is around 2.4-2.6, which is pretty incredible.

Neely Quinn: So can we break that down for a second? If a female athlete weighs 115 pounds, how much force is she producing?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: It would probably be around 265.

Neely Quinn: Most of the people who you tested at the PCC event, they didn’t even get close to that.

Dr. Tyler Nelson: The males will certainly get above that. Males can get into the 300s amount of force. For females, 260 is a fantastic score. There was a young, 16 year old girl from Triangle Rock Club, I think, that hit 260 and she weighs 110 pounds. She consequently performs really good at Nationals. She is always in the finals, she always performs very well, and her fingers are insanely strong.

If you take some of the really high level boulderers here in Salt Lake that I test – I don’t have the numbers right in front of me – I think 320-330, people are hitting those numbers.

Neely Quinn: And those are males who weigh 140-170 pounds?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: They weigh 165 pounds or probably more than that because I know some of them are 2.3-2.4. That’s the strength-to-weight ratio of a really high level boulderer. Generally speaking, the strength-to-weight ratio of a really high level sport climber is not as significant for peak force.

That’s the other thing you can do with a tool that measures force and time. For a high level sport climber, they’re not going to have as high of a strength-to-weight ratio because they don’t need as much peak finger force as someone who’s mostly doing 4-5 move hard boulders. With those athletes we can get a better idea. We can do that just by thinking about the physiology of parts of their athleticism that really allows them to be at their peak level and we can try and manipulate others that want to get there to match that same level of physiology-like adaptation.

Neely Quinn: How different is it between boulderers and sport climbers?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: Oh I don’t know the numbers right off the top of my head. Most sport climber strength-to-weight ratio is probably – I don’t know. I don’t want to throw that guess out there. 1.6 strength-to-weight ratio for peak finger force? 1.5-1.6.

Neely Quinn: So even if it’s close to that it’s substantially different than the boulderer’s.

Dr. Tyler Nelson: Oh for sure. It makes sense that it would be and that’s not a surprise to anyone, necessarily.

The other thing that’s really cool that we can measure that I find really interesting is if we take a high level boulderer and we have them pull for 10 seconds, usually they dip off at around 6-7 seconds where most sport climbers power through 10 seconds. Then we do a 30-second pull on them and the boulderer for sure is maybe 8-9 seconds and because it’s a second try, they start to drop. Some of the high level sport climbers, like 5.14 level, can hit 20 seconds. I think that was the best I saw. They stayed at 80-90% for 20 seconds which is incredible. Their peak force wasn’t very high but they could stay within 90% of that for 20 seconds.

Neely Quinn: That’s really interesting.

Dr. Tyler Nelson: Which is why they’re a 5.14 sport climber.

Neely Quinn: Yeah, but what about a 5.11 climber who wants to be a 5.12 climber? Are you even testing anybody like that?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: We do for sure. I just did an athlete that we tested this morning that is trying to go climb El Cap. He climbs 5.12 trad, or that is what his goals are. They’re going to climb Freerider and his goal is not to free every pitch, his goal is to climb all the 5.11s. For his test, his fingers weren’t that strong. He came about body weight at his finger peak force, or maybe it was 10 or 15 pounds over his peak force. His effort was great, he stayed at 90% for almost a complete 10 seconds. For him, we’re going to start training his fingers and I think he’s my age or a little bit younger so I’m totally okay with adding a little bit of weight to his body to do some repeaters.

After we did the 10-second test we did 6/3 x 10 aerobic power interval tests because at about 6 seconds you’re going to be gripping the wall then you’re going to release for a second. I think the last numbers I saw from the ROCA was like 5-6 seconds that people spend on a hold if they’re trying at their limit and then they’re releasing, so the 6/3 made sense to me.

When we did 6/3 for him, he could only do 4 sets where he stayed above 90% of his peak force. That means if I’m going to actually create a program for him that’s going to make him adapt and not just make him really tired and get him hurt, I’m only going to do 6/3 repeaters with maybe 10-15 pounds added for only 4 sets to start. Then he’s going to take equal amount of rest or longer and then we’re going to do that again and we’re going to cycle on and off. We’re going to fluctuate the weight and we’re going to fluctuate the time under tension to create that adaptation. That’s the specificity that can come from having a custom strain gauge where there’s no way to know that kind of information without it.

Neely Quinn: But wouldn’t it be – obviously you know better than me – if you’re trying to make his strength-to-weight ratio better, it seems like you would just do max hangs to get him really strong.

Dr. Tyler Nelson: We’re doing a mix and I like to do this with a lot of people. We’re doing two-a-day training where he climbs and does the climbing portion of his training and then later in the day he does his finger training portion so we’re doing both. We’re doing a max effort isometric, a portion for recruitment, and then we’re doing more of a volume program where we’re fluctuating around that peak force and changing the time under tension and the work-to-rest ratio so he can get the adaptations in the muscles that happen.

When it comes to longer hangs, it’s all about the physiologic adaptation that happens with the mitochondria and the capillaries and the energy systems that you use versus the high intensity isometrics, which is just all about maximizing your recruitment. You can train both of those.

If I were to just give him one program – set weight, fluctuate the weight – it’s way less specific to him as an individual and the likelihood that he gets overtrained with it is much more likely.

Neely Quinn: Sorry – when you said the 6/3 repeaters, how many reps are they doing without rest?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: This particular individual, I only prescribed four until he needed a longer rest. Then we’re going to do five rounds to start with that.

Neely Quinn: Okay. 6/3, 6/3, 6/3, 6/3, 6/3 then rest.

Dr. Tyler Nelson: I think we did 60 seconds of rest and then the same thing and we’re going to do that five times to start and then see how he feels.

For my local athletes, I test them every couple weeks. Every couple weeks I want to see the adaptation that’s happening and then we’re going to make any fluctuations on the program based on that.

My background is in Division I level college football strength and conditioning, right? Way different. Most climbing coaches are like, ‘Oh my gosh, that sounds like so much testing and reassessment,’ but that’s what they do at the Division I level so that’s just what I’m used to. I’m used to having an athlete test then having an athlete retest and having them make program fluctuations. That’s kind of my background and that’s what most sports do and I think it’s really important. It’s really easy to see if athletes are not adapting to your program and you’ve got to make changes to it but it requires a lot of work. It was a lot of work and a lot of understanding what’s going on inside the skin.

Neely Quinn: Gosh. You have to know a lot to really make good use of this data.

Dr. Tyler Nelson: Therein lies why those gyms are having me come teach conferences and show their coaches how to use the tool and assess a bunch of athletes that are interested in getting readouts of their numbers. I think in general, I would characterize climbers as pretty nerdy. Climbers, for the most part, are pretty psyched about numbers and trying to find ways to get stronger that they can actually visualize and see. I have tons of friends, and it doesn’t matter good or bad, that are climbers that are engineers or physicists. I’m not sure why that is.

Neely Quinn: We’re definitely a nerdy bunch.

Dr. Tyler Nelson: It seems to be the case.

Neely Quinn: It seems like a lot of those super nerds would want to spend the thousand dollars and just use it on themselves.

Dr. Tyler Nelson: Oh yeah. I have one pro athlete, this 5.14 climber, that bought one for himself. He’s psyched. He’s a professional rock climber and he climbs routes and he wants to get to the next level so he’s all in. $1,000, if you think about a long term training career, is not that much money. Most hangboards cost $300 and you buy some weights. Like at my office I think my weight rack was $2,000 so it’s really not that much money.

It’s really just that most people maybe don’t understand how useful it really is because it gets into the details of athlete programming and physiology, which for someone like myself, is just mind-blowingly cool for the things that we can do with it.

Neely Quinn: Is there anybody else that you know who is doing anything similar to you? I’m sure a lot of people are like, ‘I just want to go to Tyler and have him test me and train me,’ but you’re in Salt Lake so is there anybody else like you?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: I’m sure there are people that are doing testing. I know Eric Horst does and I’ve talked to him a bunch on the phone. I know this Doctor, David Giles, who lives in the UK, I think, who is a researcher doing climbing research. They’re psyched about doing data analysis and measuring these types of things and VO2 capacity in climbers. Mostly research groups. I don’t know many private coaches that are doing it.

I know coaches that are interested in what I’m doing and that we’ve taught at the PCC that are applying these principles like the Boulder Lounge that I’m going to do a seminar at in March. Their coach, Harlan, is super psyched and wants to learn how to do this kind of stuff so he bought one of the strain gauges and I’m going to go train him how to use it.

The thing that’s really cool is that this stuff is just now becoming affordable for coaches. Unless you have a sports science background like I do and you’re a training coach, you don’t really know what’s out there. It’s hard to know exactly what there is to do out there. There’s so much information out there it’s like, ‘What is good and what do I need to do?’ I think now it will become much more popular to use things like this because I’ve even chatted with Tom Randall from Lattice. He’s going to come into my office on Monday and we’re going to hangout and chat and do a bunch of testing stuff on my strain gauge. He would agree that the future of testing fingers is with some sort of strain gauge like this because it’s just safer to use, it’s more accurate, and we can make better programming decisions based on that.

Neely Quinn: Yeah, it’s really cool that other trainers are getting involved in this.

Dr. Tyler Nelson: It’s just slow. It’s like anything. Most people that do what they do and are good at what they do and are helping people, they’re going to be like, ‘I don’t care. I don’t need to do that,’ and that’s totally okay. You really don’t. It’s not essential, at all, but in terms of moving into the future, this is something that will be really popular. It’s just a matter of time, really.

Neely Quinn: Is there anything we missed about the app that it does?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: The app isn’t even made yet so that’s a hope. I sent Greg a big 120-page Powerpoint about exactly what I would like the app to do so whether or not that all gets exactly done like I suggest is kind of out of my control. It comes down to people having the funding for making the app and the app developers need to get paid for their time, too. I’m not exactly sure what the app is going to look like completely. That’s why even if the app is not exactly like I suggested and want, I’m going to have my Excel spreadsheet ready to go so if people get their strain gauge and they’re ready to use it we’re going to use that tool as well. It’s fine and it’s not any more work, necessarily, it just won’t hook to a smart phone which won’t be as sexy in that sense but it’ll have all the good information.

Neely Quinn: But at the PCC you were using something. You were getting people’s data off of the strain gauge.

Dr. Tyler Nelson: Yeah, you get a readout. That’s just a free application that hooks Bluetooth to the strain gauge and you’ve just got to program it to kick out data. The downside of that is it just gives me raw numbers then I need to copy and paste those numbers and I’ve been doing this for a year. It’s kind of annoying and it takes a little time to copy and paste numbers into an email then send it to myself where this new application will go to a computer or a smartphone application so you don’t have to do that. It will get rid of those steps and all I’ll have to do is put it into my Excel spreadsheet and then it gives you all the cool metrics.

Really, coaches and the coaches that have come to my office and have tested with this and seen it, they’re mind blown by the types of information you can get. It’s really not as complicated as it sounds. The physiology is but the application and how you would use it sounds much more hard than it really is. Most people would understand it and be like, ‘Wow. That makes a lot of sense.’

The last time Eva Lopez came to Salt Lake we chatted with her and she had an evening that we went and listened to. People were asking her questions about finger training and she was like, ‘I don’t know. I don’t know you.’ In terms of what’s best for an individual, what you should cycle on/cycle off, small edge, max weight, she doesn’t know. No one really knows. The only way you can know is if you have some way to measure how much force someone can produce over time and it’s really easy to understand that that is the #1 metric that you could use to give someone a much better finger training program. There’s no way to know other than having that capability. Broken down to that, it’s the most simple thing that it’s so amazing for. You can give very prescriptive information for someone just based on the amount of force they can produce over time.

Neely Quinn: That’s what we all want. We all want a program made for us.

Dr. Tyler Nelson: I can work it up to make it sound really complicated because I kind of have a problem with doing that but simply put, that’s what it is.

Neely Quinn: Do you have a sample of anybody’s data that you would be willing to let me put on this podcast page?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: Oh sure. I can ask a couple of different people if you want, like if you’d be interested in looking at a boulderer, a sport climber, maybe compare those two or maybe some youth athletes. What do you want?

Neely Quinn: Anything you could give. I think it would be interesting to have a few to compare and we don’t even need names. It could just be blocked out but I think that would be cool to have for people.

Dr. Tyler Nelson: For sure. I’ve got lots of that.

Neely Quinn: I think that’s all of my questions about it. Is there anything else you want to mention?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: Not that I can think of. That’s most of it. If people have questions they can contact me. I get lots of messages a day that I try and answer for people with questions like that. If people are psyched about learning more about it I’m just now in the process of organizing my spring/summer calendar for clinics and I have quite a few lined up already. If people are interested we can set those up as well but I think the more that I talk about it the more it might be confusing.

The real thing that I wanted to cover was the ability to measure your anaerobic and your aerobic power and capacity. That’s really cool and there’s no way you can do that. Well, there’s ways you can kind of try to do that by working on a wall but this is a much quicker and a much more accurate way of measuring those aspects of climbing.

Neely Quinn: Do you feel like we got to that enough or do you want to talk about it more?

Dr. Tyler Nelson: I think we got enough of that.

The other thing that’s kind of specific about testing is if you’re doing testing and you’re doing movement testing, which climbers have done classically and I’ve done this on a lot of athletes and I think it works still, is using a systems wall. I know Steve is a big fan of doing this where you’re measuring someone’s anaerobic capacity and you work them at 85-90% of their intensity load. You work them for sets with x-amount of rest and you measure how many rounds they can do. I do this with remote clients a lot and that works really good but as soon as you take the skills out of it you get a much more accurate representation of the actual forearm muscles and the physiology.

People would argue, ‘Yeah, but it’s climbing so you want the skills involved.’ Well, kind of, but if I’m really trying to get some good data on what their body is capable of at any given movement, I want to take the skills out as much as we can because then we can give better prescriptions on what we really think they should be doing. It’s easy to mess up footwork or movements if you’re climbing to fatigue. There are lots of variables and most testers and scientists would want to take the skills out as much as you can and really focus on how much force the muscles can produce, for how much time, and how much rest they need.

Neely Quinn: I mean, it could be motivating for people to know, like, ‘I’m super strong but my skills suck,’ or vice versa.

Dr. Tyler Nelson: I think in general, and the fun thing about it is most kids are just really excited about it. The kids that I have tested on, getting them to be so psyched about the testing and the last time I tested the Momentum team, this group of teenage girls were screaming so loud I needed earplugs. My ears hurt they were so psyched for their teammates. It’s a type of team building exercise where everyone gets tested. I got so many messages from these team members afterward like, ‘That was so sweet. Thank you so much for testing us. We’re psyched.’

It’s hard for people to know. Rock climbing is hard and rock climbing competitions are hard for these young kids. If they don’t perform well they think either they’re not good or that they’re not strong enough, right? When you do testing on them you’re like, ‘Wow! You’re really strong,’ and they’re psyched. It can swing both ways but a lot of times it works in the athlete or the coach’s favor that the athletes get really psyched about getting strong. Everyone, regardless of age, wants to get better at this sport and they want to get stronger.

Neely Quinn: Yeah. I want to fly to Salt Lake and test with you. [laughs]

Dr. Tyler Nelson: It’s been fun. I have lots of athletes that when they drive through they stop by the office and test. It’s been really cool to meet lots of people from around the country when they come through and I get to test a bunch of really high level athletes. It makes it fun.

I’m really excited about this coming out because people will have more options around the country and then we can teach some people how to use the tool. The consequence is that people are going to think about training for climbing in different ways, which is good and normal. You get a lot of resistance from people who have done things one way forever and it’s like, ‘Well, things are always changing. Science is always changing and we’re always learning more so to assume new things aren’t as helpful or as effective is just kind of silly.’ That happens, too, and that’s not a problem but it will become much more mainstream as the years go on.

I’m just lucky enough that Greg reached out to me and that I was able to be a part of spearheading using one of these things and trying to figure out what the hell we can do with it for climbers. I’m pretty psyched.

Neely Quinn: Yeah, I’m psyched, too. I’m glad we have you on our side so thank you very much for talking to me about all of this. I’m sure a lot of people will really appreciate it.

Dr. Tyler Nelson: You bet. I’m psyched they’re making them. Feel free to reach out with any questions you have. I’m happy to answer them.

Neely Quinn: Thanks and I’ll talk to you soon, I’m sure.

Dr. Tyler Nelson: Okay, cheers!

Neely Quinn: I hope you enjoyed that interview with Doctor Tyler Nelson. You can find him and he’s very active on Instagram @c4hp. That stands for Camp 4 Human Performance and that’s exactly what his website is, camp4humanperformance.com.

He actually did give me some data sets from some of his athletes to put up on TrainingBeta so for this episode, and for every episode, I have an episode page on TrainingBeta. If you just go to trainingbeta.com and then go to the ‘podcast’ and search ‘Tyler’ you’ll find this episode. I put up a data set for a 10-second max hang for a boulderer, the same for a route climber, and a data set for repeaters for a trad climber. They are actually super interesting to see the differences between the boulderer and the route climber. These are like a 5.14 route climber and a V14 boulderer so it’s cool if you want to check that out.

If you want to be taught further by Tyler, like if you want to be his student, we are doing another PCC event, the Steve Bechtel Performance Climbing Coach event, in May of this year, 2019, at a gym in Fort Collins. You can go to performanceclimbingcoach.com to find out more about that.

What else is coming up on the podcast? I’m going to interview my friend, Brianna Greene. She’s one of my best friends and she recently wrote an article for us. You can find that on the blog if you just search ‘Brianna.’

She talks about how she trained to climb her first 5.12a. She had to both mentally and physically train because fear was holding her back, plus a little endurance. She had a real process for going through that and getting her first 5.12a, which I got to witness, which was super awesome to watch. Our first 5.12 is a big deal. Our first 5.11 is a big deal. She’s going to tell us about her process on the podcast and that should be out in a few weeks.

Then other than that, if you want any help with your own training and if you want a detailed, guided training program, we have a lot of those on the site at trainingbeta.com/programs. You can find something if you’re a route climber, if you’re a boulderer, if you just want to train fingers, or just power endurance. You can find those, again, at trainingbeta.com/programs.

Matt Pincus, my right hand man here, also does online personal training. You can find more information about that at trainingbeta.com/matt.

I’m not going to talk today about nutrition but if you want to be a client of mine I do nutrition consulting and you can find more about that at trainingbeta.com/nutrition.

Thank you so much for listening all the way to the end. You can follow us @trainingbeta on Instagram or Facebook. We also have a Facebook training group which you can find at trainingbeta.com/community. It will send you straight over to Facebook so you can join. I think there’s 5,000 members now which is pretty awesome. People are pretty active in there talking about training methods and injuries and stuff like that.

Alright, I will stop talking now. Thanks so much for listening and I’ll talk to you soon.

[music]

Cool, thanks for the podcast!

It doesn’t say what grip is used for the pull test, half crimp?

Also is it done seated with a thigh pad holding one down, like in a lat pull down machine?

trying to put it in context, thanks

Hi Frank – Yep, half crimp and seated like the photo of Puccio at the top of the page. Good luck!