As a coach, I have taught clinics, recorded podcasts, written articles, and had countless conversations about helping climbers improve their tactics with the aim of making their process for working, and eventually sending, routes and boulders more efficient.

While I still think tactics are extremely important and an area most climbers can improve, my understanding of them has become more nuanced. I now believe that efficient sending really comes down to balancing having a tactical approach with being willing and able to simply try really damn hard.

For years, I have thought in my own climbing and preached in my coaching that it is wise to delay giving send attempts until you have not only done all the moves, but also done the links that will lead to success. I now believe that waiting this long to start trying hard from the start is a mistake and should be strategically worked into the process at an earlier stage.

To be clear, I still think tactics – like those I outlined in this article – are a prerequisite in the early stages of the projecting process. There’s no disputing that you need to learn the beta, find rests, figure out where to clip, and identify the cruxes. Simply trying hard from the ground every time isn’t an efficient way to send a route. The more systematic you can be in these early stages the better you’ll be able to apply what you’ve learned on one go to do better on the next, and the sooner you’ll be ready to give true redpoint efforts. Being really deliberate and tactical in the early stages of working a climb makes the whole projecting process more efficient.

That said, when exactly do you start simply trying hard from the ground? Is it as soon as you know all the beta? Are there certain links that are prerequisites? I don’t think there’s a single “correct” answer here, but I can say that asking these questions and evaluating your tendencies will make your projecting process more efficient in the long run.

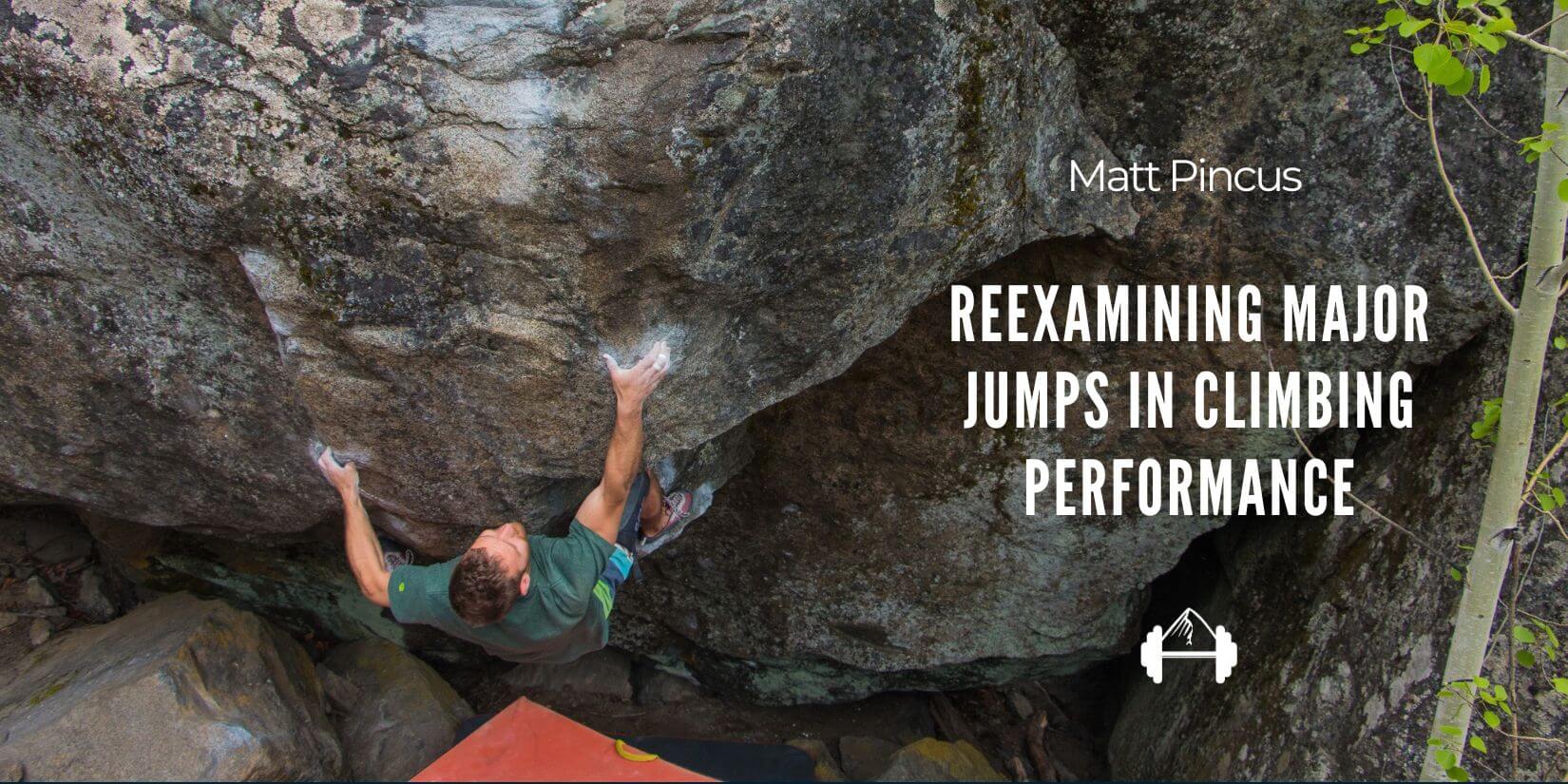

Matt Pincus climbing Crosstown Traffic 5.13d | Photo: Nate Liles | @orographic_visual

A Hypothetical Route

To help us navigate the above questions, let’s look at a hypothetical route. This climb starts with some intro climbing to a hard boulder, has a sustained middle section, and finishes with a hard redpoint crux guarding the chains. Remember, in this example, we have already tried this route and know the beta well and are debating whether to try to link sections or give all-out efforts from the ground.

Prioritizing Links with Top-Down Thinking

Were a climber to choose to prioritize top-down thinking, it would look like doing logical links from lower and lower on the route to the anchor. On our hypothetical route, they would likely not yet worry about making it through the opening boulder from the ground and would instead focus on starting at lower and lower points within the sustained middle section and try to climb through the redpoint crux from there.

When prioritizing links in this way, the thinking is more top-down rather than ground-up. This is a really important tactic and one of the most common ways I coach climbers to improve their tactics. The logic behind this approach is that simply getting higher up on a climb doesn’t mean much if you don’t really stand a chance of actually sending. So, to avoid falling into this trap of getting geographically close to the anchors without actually having a chance of clipping the chains, a climber would go bolt-to-bolt up to progressively lower and lower starting points to build consistency and confidence in their ability to execute high up on the route even when fatigued.

Try Hard from the Ground

On the other side of the spectrum is starting from the start every try and trying to send. A climber taking this approach on our hypothetical route would focus on making it through the opening boulder and then proceed bolt-to-bolt through the rest of the route once they had fallen.

When trying from the ground, every attempt is about trying to send or push the high point further up the wall and any climbing done after the initial fall is simply to keep the beta fresh in the climber’s mind. It’s also important to note that with this kind of thinking every attempt, at least in theory, has the chance of sending.

Benefits/Drawbacks of Each Approach

As I said above, I do believe that both of these approaches have their merits as well as their pitfalls. Evaluating the relative benefits and drawbacks of each approach on our hypothetical route will help us determine when one is more appropriate than the other.

Try Hard from the Ground Every Try

Benefits:

- You practice giving 110% effort from the ground.

- You are rehearsing the hardest section of this hypothetical climb – the opening boulder.

Drawbacks:

- The bottom of any route is going to get more of your attention than the top.

- Lessons about whether your beta is good enough on a particular section are only learned when you get there from the ground.

- Learning higher on the route is limited by these sections being geographically higher up.

- Going bolt-to-bolt doesn’t give you an accurate sense of what a section is going to feel like from the ground.

Prioritizing Links with Top-Down Thinking

Benefits:

- Low-pointing/doing big links lets you “pressure-test” your beta and better simulate what sections are going to feel like from the ground.

- Lower links build confidence that you will be able to execute the redpoint crux and still climb to the chains when fatigued.

- You learn valuable lessons about where you need to practice or further refine your beta without having to wait to reach this section from the ground.

Drawbacks:

- Linking the hard opening boulder from the ground is neglected until the upper links have been done.

- You aren’t practicing pulling on and giving 110% effort from the ground.

- There’s a big difference both physically and mentally between doing big links or really low, low points and actually sending.

- Waiting to even give yourself the possibility of sending from the ground doesn’t let you practice being in that headspace.

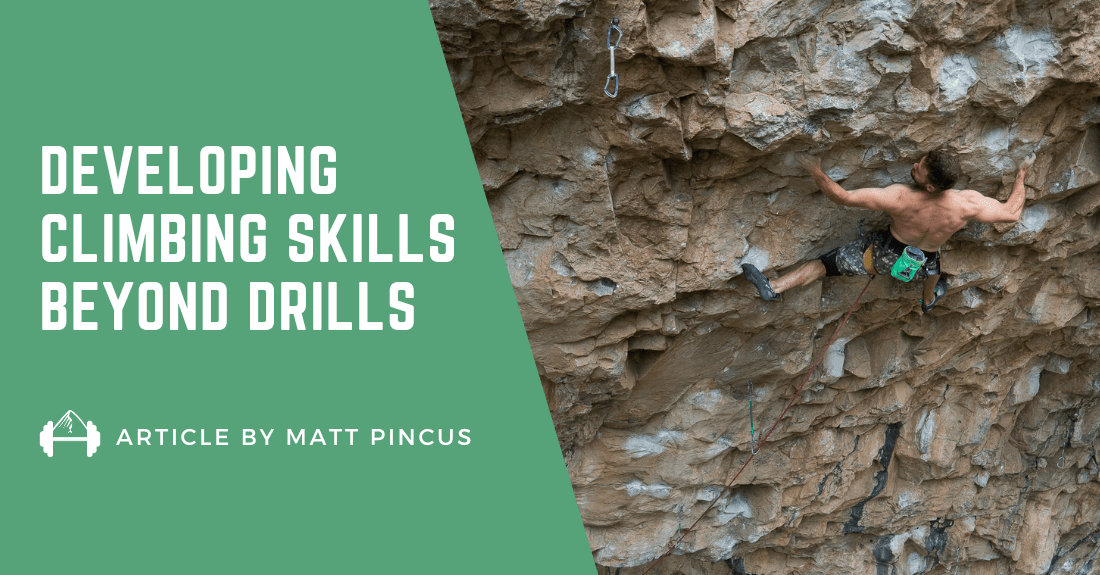

A climber on Florida 5.14b in Rodellar, Spain | Photo: Matt Pincus | @mpincus87

Finding Balance

If we accept that both of these approaches have their merits as well as limitations, it’s pretty obvious that our goal should be to find a balance between them so that we can utilize each one’s benefits while avoiding their drawbacks. The next logical question is how to find this balance.

Again, let’s return to our hypothetical route.

The issue with just trying from the start is that we aren’t going to know if we’ve optimized our beta for the sustained middle section or the red point crux until we get to each of those sections from the ground. This is inefficient as we want to minimize the number of times we have to fall up high on any route.

On the other hand, the issue with only prioritizing low-point links is that we aren’t practicing flipping the kill switch and attacking the bottom portion of the route with the intention of climbing through it. Additionally, while your upper links will have let you optimize your beta for those sections, you won’t have done so for the opening boulder and will have to spend attempts that could be true send attempts doing so.

On our hypothetical route, I think the answer is fairly simple: do both. There’s no reason you can’t try hard from the ground and then transition back to thinking out and trying to do the next logical link once you’ve hit the end of the rope. In an ideal world, you would steadily move your high point up the route and your low point down the route until they met and you sent. If this didn’t happen, you could simply emphasize either ground-up or top-down thinking each go or day based on where you feel like you were struggling on the route.

The important takeaway here is that by doing both early in the projecting process you aren’t handcuffing your learning anywhere on the route. As projecting is all about learning before executing, this should let you send quicker even though it’s more work upfront.

Tendencies

Ok, talking about this in hypotheticals and using an imaginary route is great, but we have to actually climb real routes and it can get way more complicated when our tendencies, egos, and fears come into play.

My advice here is to think of your projecting approach as lying on a spectrum with top-down thinking on one side and ground-up thinking on the other.

First, examine your tendencies. Do you tend completely toward one end of the spectrum or the other? If so, consider shifting your thinking a bit more centrally as an experiment. You may surprise yourself and end up sending faster than you expected. If you don’t tend towards one end of the spectrum or the other, you should still experiment on your next project. It’s only one route and you don’t know what you don’t know. The rest of your climbing career will thank you.

Next, if you consistently trend towards one end of the spectrum, you should evaluate why. Do you need to have the possibility of sending to really try hard? Do you shy away from doing links because they feel like a waste of time? Are you the climber that always comes up with another link you “should” do before going for the send?

The answers to these kinds of questions can reveal a lot about how we frame our projecting mentally and is a big topic beyond the scope of this article. For now, it’s worth acknowledging that this kind of self-reflection and analysis is never easy. The answers might make you feel uncomfortable, but it’s worth the effort. If you plan on continuing to climb for a long time, you will likely spend quite a bit of your time immersed in the projecting process, so figuring out not only how to make it efficient, but also how to enjoy it is really important. Again, the rest of your climbing career will thank you.

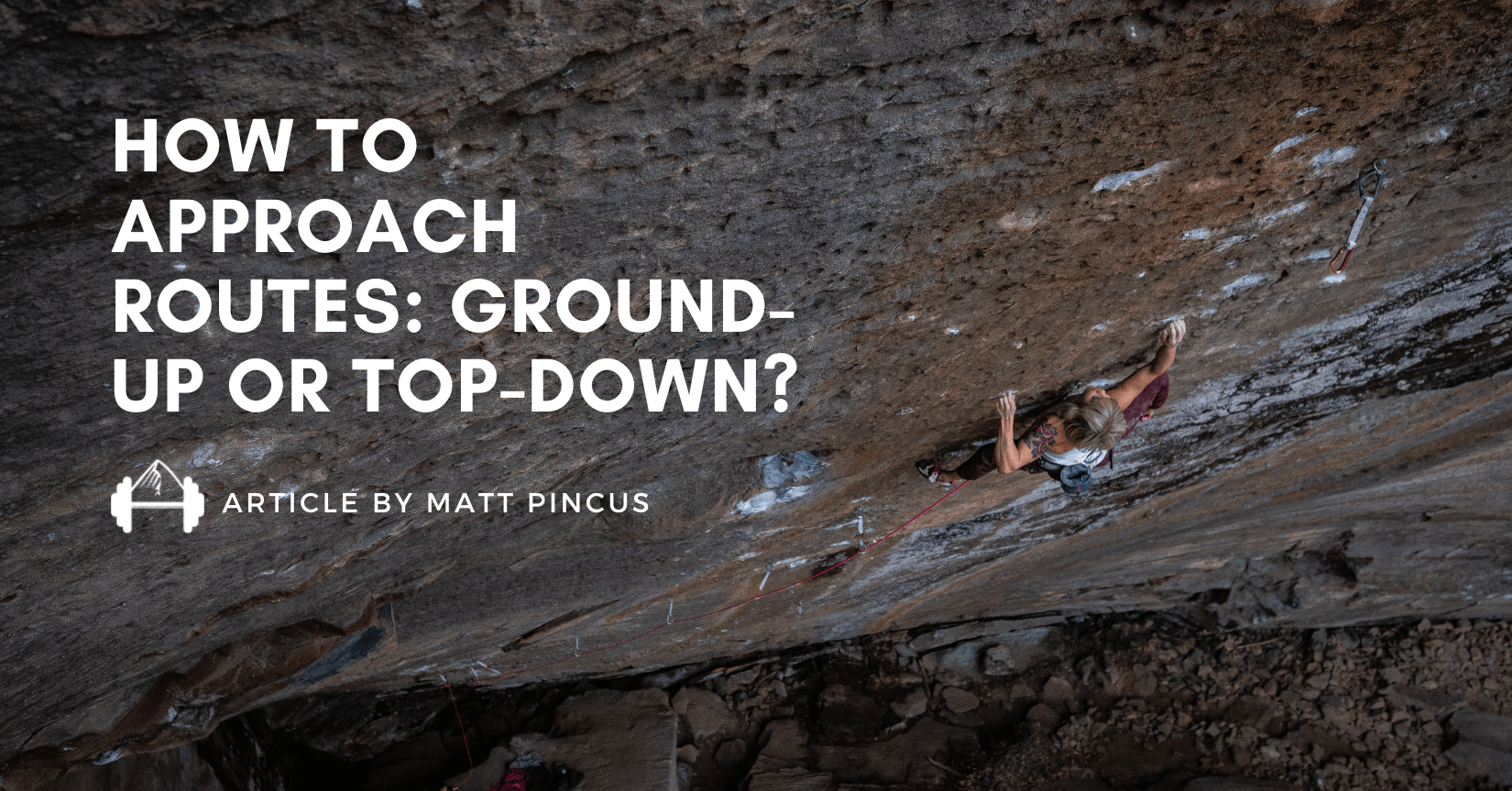

Cover Photo: Anna Liina Laitinen on Pure Imagination 5.14c in the Red River Gorge | Photo: Matt Pincus | @mpincus87

About The Author, Matt Pincus

Matt is a boulderer and a sport climber based out of Lander, Wyoming. He splits his time between training at home in Lander and traveling to pursue his climbing goals around the world. Matt is also TrainingBeta’s head trainer. He’s a seasoned climber and coach who can provide you with a climbing training program from anywhere in the world based on your goals, your abilities, the equipment you have, and any limitations you have with time or injuries.

Train With Matt

Matt will create a custom training program designed to help you target any weaknesses so you can reach your individual goals. Whether you need a 4-week program to get you in shape for an upcoming trip or a 6-month program to make gradual strength gains, he’ll create a weekly schedule of climbing drills, strength exercises, finger strength workouts, and injury prevention exercises tailored to your situation.

Photo: Nate Liles | @orographic_visual

Leave A Comment