A PT’s Analysis of Neely’s Movement While Climbing and How It Relates to Injuries

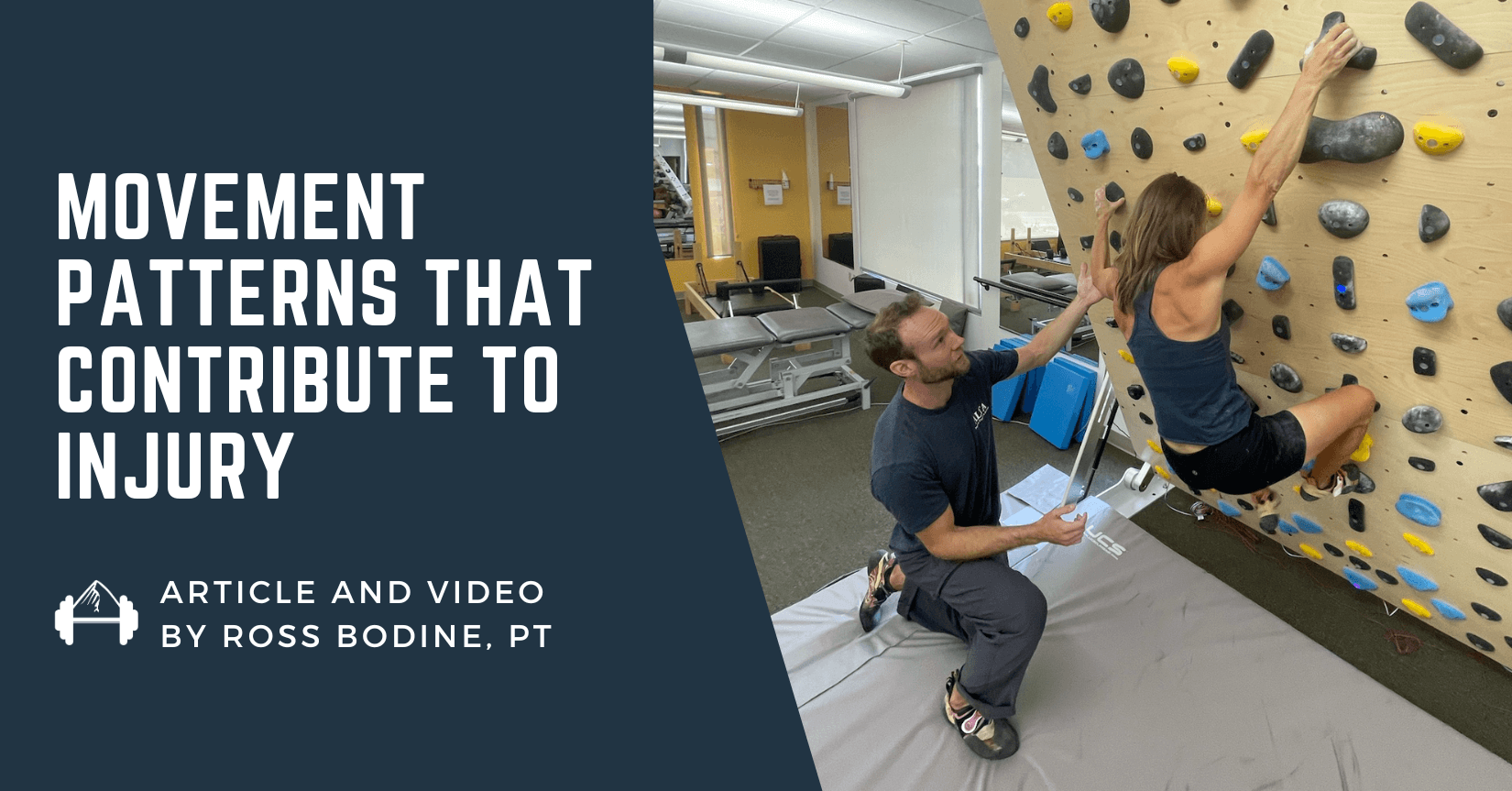

This video and article were put together by Ross Bodine (Neely’s Physical Therapist). Ross Bodine, PT, DPT, FAAOMPT is a fellowship trained physical therapist that works at Alta Physical Therapy and Pilates in Boulder, Colorado. He specializes in identifying and correcting aberrant movement patterns in climbers before and after injury.

This video highlights the subtle movement dysfunctions that can occur on one side and not the other with the aid of a symmetrical climbing system, like the Grasshopper Board. These aberrant movements often occur from weakness or disuse in the shoulder and result in increased stress further down the arm that can result in pain. Ideally, these movement patterns are just corrected on the wall, and we train them on the wall with no additional exercises.

However, sometimes we require a little bit more coaxing to break out of the stuck movement pattern before adapting these movements back onto the wall, as this video also demonstrates later on. I’ll also introduce the concept of Movement Boarding where you perform repetitions of the same move, moving your body around a fixed elbow. Unlike hangboarding when you are static, Movement Boarding allows you to train a movement that you may struggle with on one side vs the other side.

For those of you interested in in checking out Grasshopper’s Climbing Wall Systems, and hoping to save a little money, use the Coupon Code: RossB.GH.2022 to save $500 off the Ninja Model.

https://grasshopperclimbing.com

Here’s a litle more explanation of Ross’ thought process:

2:16 – Slow Motion Breakdown of Chosen Movement Patterns Side to Side

I started my examination here because Neely wasn’t complaining of any pain at the time When her pain does occur, it is climbing specific (i.e. nothing else aggravates it), located in her right wrist, or her right forearm. Notice the decrease of control in the right shoulder at 2:30, causing the elbow to move in and out, while the left elbow is still. I actually didn’t notice this at the time of examining her, only when I started slowing down the video and looking at it side-to-side to notice it. I did notice the elbows kicking out at the 3:00 minute mark, as they both moved out. And I’ll start just by addressing that.

3:13 – Beginning To Correct The Obvious Movement Dysfunction

Even though this move did not bother her, this movement is common in climbers with upper extremity pain, so I jumped in to work on that. Notice how it is much easier for her to correct it on the left compared to the right, meaning her right side is much more rigid in its choice of movement. When this rigidity of movement patterns occur, the body gets stuck in the same movement pattern and will stress the same muscles/tendons/ligaments through the upper extremity more than if it could move in a variety of ways. This can lead to tissue breakdown and injury.

There is also an effect centrally in the brain as movement patterns become less diverse. The brain likes to take short cuts, and its job is to recognize patterns to predict the body’s response. If the brain starts to sense that a specific muscle firing pattern usually results in pain, it will say it is painful (even before it gets the body’s signal). Pain can even occur when thinking about doing a movement. An example of this is your body’s response to watching Honnold in Free Solo, as you could probably feel your heart rate increase and your palms start to sweat (even though you logically know the outcome of the film). Even after the injured tissue has healed, the pattern of muscle firing can result in pain, or it could go more unnoticed as you would either consciously or subconsciously avoid the movement. This pattern will likely continue, unless it is broken up by creating a new movement pattern.

Muscle wise, Neely likes to rely on her Rhomboid and Posterior Deltoid to pull herself up. While I am asking her to use more Teres Major, and Serratus Anterior. At the end of the video I will go more in depth and give Neely on-the-wall climbing drills to work on to help break this movement pattern.

5:52 – Comparison Of Painful Attempt vs Non-Painful Attempt

Comparing Neely’s movement on a move that was painful the first time, and not painful the second time, really helped to shed some light on some of her core insufficiencies that can be contributing to increased stress and pain in her right arm. On the non-painful attempt she was:

- Higher Up and Got Higher Sooner – Her elbows were more bent and pulling her up more

- Shoulder Blades Pushed Apart – Part of this is from her shoulders engaging more from rotator cuff activation, the other part is from her right hand pushing her body left over her left foot.

- Pulling her Right Hip Up and into the Wall – This will come from actively using her lats to lift her pelvis up, rather than resting into the lat hammock. Her whole core is also working a lot harder to create stiffness that allows her right hand to push herself over her left foot.

7:04 – Hanging Analysis

I could have jumped straight into what I would like Neely to work on, on the wall, but I also know she likes to hangboard for training. To maximize the benefit of her sessions to strengthen her shoulders as well as her fingers, I try giving her more options to hang in. Right off the bat, Neely likes to hang with straight elbows, with her elbow pits facing each other. Those are both potentially problematic.

The problem with straight elbows is that:

- This positioning will put your shoulders at a muscular disadvantage since your muscles are usually less efficient or forceful near their end ranges – making them weaker with less endurance.

- When the elbows lock out, they will no longer disperse any of the forces through the upper extremity. This puts all the excess torque into the ligaments of the wrists and less engaged shoulders.

- For the elbow in particular, the tendons will be more compressed as they stretch over the elbow bone (more so when hyperextended) which can lead to tendinopathy.

- Hanging and climbing with straight elbows will conserve energy as you rely on ligaments and tendons’ passive tension. Hanging is always a training activity, where climbing can be for training or performance. Why would you “train” at a lower engagement level with straight elbows and only train your passive tension? Actively lifting yourself up with your shoulders will generate active tension within the muscles, leading to stronger muscle contractions. There is a time and place for straight elbows (when resting during send burns), but training is not one of them. Unless you need to work on the skill.

The problem with internally rotated shoulders:

- The Lats and Pecs are working harder than the rotator cuff, and the humerus is getting pulled out of its ideal overhead position. Note: The lats and pecs will always be stronger than the rotator cuff, but the rotator cuff needs to be strong enough and active enough to hold the shoulder in place.

- There is a strong possibility that the scapula is not fully upward rotated which can irritate the rotator cuff and engrain a single movement pattern.

- Being able to unlock the humerus on the scapula from a dead-hang to an engaged shoulder is often the most difficult movement for a climber’s shoulder. Training the engaged shoulder position will help expand these movement options.

From what I have found with my patients that have pain in their upper extremities from hanging, they generally all hang with straight arms and focus on pulling their shoulder blades down and back. That pain goes away when they bend their elbows (from pulling themselves up with their shoulders, not by flexing their biceps) and lifting the bottom corner of their shoulder blade up towards their elbows (which will help the rotator cuff pull the humerus back into the center of the joint).

I tried many different positions (pulled up higher, with feet on, etc) without getting what I was looking for with hanging. I was also starting to aggravate Neely’s bicep, because she likes to use her Biceps to bend her elbows rather than her shoulders. I would have loved to be done with the movement correction here, but we struggled in achieving my “ideal” position. But, if climbing and hanging in various positions is not achievable, I move on to muscle activations.

10:46 – Off-The-Wall Muscle Activation: Pivot Prone and Y’s

I moved here on to a couple off-the-wall exercises because I wasn’t quite getting the change of position on the wall I wanted. I started with Pivot Prone (which is named after a movement pattern that infants go through) because that is where Neely can activate her rotator cuff more easily. Keeping your elbows down, barely on the ground is the first key to get the correct muscle activation in the rotator cuff. The second key is the hand position trying to reach the pinky back toward the shoulder to get proper serratus anterior activation. Most people know to strengthen the serratus through a push-up-plus movement. But how often do you do this when climbing? On a reachy mantle? (But those aren’t that common in most forms of climbing) Serratus anterior is the only muscle that posteriorly tilts and externally rotates the shoulder blade which are enormously important during all movements of the shoulder (even pulling – the complete opposite of a push up plus).

Most people are familiar with the Y exercise for the Lower Traps, although, this exercise is also training the rotator cuff, and serratus anterior when positioned properly. Maintaining the elbow pits rotated up toward the ceiling is key for this, and often overlooked. When it is overlooked, the deltoid with

I like starting out with 1-minute holds in each position as this really starts to engage the stabilizers, and makes it sufficiently difficult for your brain to focus on. Having the exercise be difficult to engage the brain helps cement the movement/position and help make those muscle firing patterns translate to other activities. But climbing doesn’t involve holding the same position, so we add a transitory movement between these two positions to help “unlock” the humerus on the scapula. This aims to create more pulling from the humerus on a stable scapula maintaining its posterior tilt and external rotation (keeping serratus engaged through the movement).

13:35 – Off-The-Wall Muscle Activation: Rotator Cuff Specific Activation

All of my preferred shortcuts weren’t quite working. So I took a step back and went through more of a “standard” examination looking at muscle strength, nerve mobility and symptom modification. Upon testing I found: ulnar nerve tensioning increased Neely’s forearm pain, and resisted wrist extension increased her wrist pain. Both of these tests were asymptomatic after I had her draw the head of her humerus (her actual shoulder, not her shoulder blade) back into the table.

This posterior draw comes from the four rotator cuff muscles working in concert with each other to shift the head of the humerus to be more centered in the joint, as most climber’s (and people in general) painful shoulders sit too far forward. This anterior glide of the humeral head is due to stronger and stiffer lats, pecs, posterior delt, that will all shift the head of the humerus forward when contracted, if the rotator cuff isn’t doing it’s job and keeping the head of the humerus back. This anterior glide of the humerus can increase the tension on the ulnar nerve as it passes in front of the shoulder. When lacking proximal stability and engagement of the shoulder, the head of the humerus can also get pulled further forward when resisting wrist extension, putting more strain on the forearm musculature.

In order to more specifically wake up Neely’s rotator cuff, I am asking her to keep her shoulder (again, not shoulder blade) pulled back into the table as I resist various motions at her shoulder, elbow, and wrist. It is much easier for her to find the cuff engagement in this position because the shoulder is in a more neutral position, she has the feedback of the table to press back into, and she has no predetermined movement pattern with hanging or pulling. I also wanted to make sure she wasn’t pulling her shoulder blade “down” towards her hip, as most climbers like to compensate from a lazy rotator cuff with their strong lats.

16:35 – On-The-Wall Training – Movement Boarding

Leave A Comment